My research for my MA thesis has had a nice overlap with the accounting ethics class which I am TAing for. Students have been learning about the benefits that corporate social responsibility (CSR) has for businesses. The students learn that there are various benefits from CSR which may lead to greater profitability in the future, such as a competitive advantage, the ability to attract better job applicants, and a better reputation. But, must that be the case or is it only contingently so? Here, I want to put forward two arguments. The first, is that the practice of CSR leading to higher profitability is only contingently the case, not necessarily the case. The second, is about the way we contrast CSR to “single bottom line” or “profit maximizing” strategies. My contention is that it is important to contrast the two as practicing CSR is only contingently a profit maximizing strategy.

Corporate Social Responsibility and the Triple Bottom Line Agenda

One way of thinking about CSR is the “triple bottom line”, a term originally coined by John Elkington in 1994. The triple bottom lines asks companies to not only be concerned with profits (single bottom line) but to also concern themselves with community and the environment. This led to the “3P formulation” of “people, planet and profits”. Elkington argues that the push to practice triple bottom line thinking arises through seven “global cultural revolutions”. They are the following:

- Markets – Companies are under greater pressure from competition both domestically and internationally

- Values – Shifting societal values have lead to consumers caring a great deal about how the companies they purchase from treat others

- Transparency – The actions of companies are becoming increasingly clear to consumers and companies must therefore be more conscious of the actions they take as they are under more scrutiny

- Life-Cycle Technology – A new focus from consumers on the sustainability of how products are made and how they can be disposed

- Partners – Companies are driven to partner with other companies that they would have previously seen as competition in order to achieve success within the new environment

- Time – A demand for companies to be more far-sighted in their decision making

- Corporate Governance – A dramatic shift in our conception of how businesses should be run including a change in ideas about who should run companies and who companies should serve

The Positive Correlation between CSR and Profitability is only Contingent

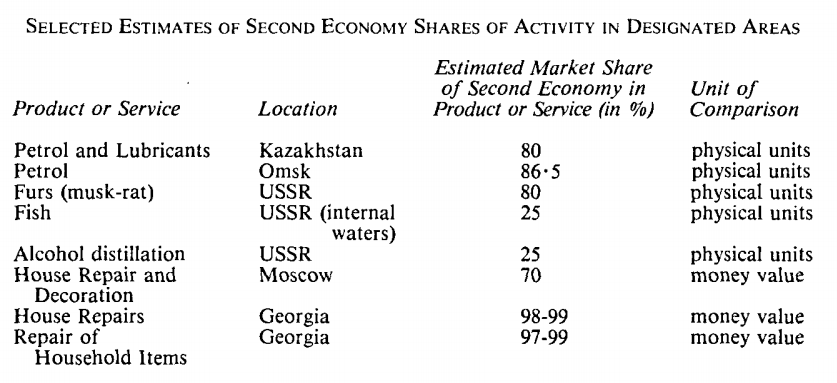

In the undergraduate accounting ethics course that I am TAing, students are taught that practicing CSR can not only make a company act more ethically but can also help companies increase profits. The empirical evidence for CSR’s profitability is somewhat unclear as Table 1 shows here. What’s interesting to note about Elkington’s push for the triple bottom line is that it is necessary only in light of changes in consumer preferences and the actions of competition. That is to say that there are specific requirements about social reality that need to be present in order for the triple bottom line strategy to be effective and, as students are taught, help increase profits. Thus, if these social conditions are not met, then it’s possible that the triple bottom line would not be effective at increasing profits. For example, if consumers did not care at all about the sustainability of their products, then there would be no reason to develop “Life-Cycle Technology”.

Thus, CSR does not necessarily align with increased profits and it is only contingently the case that they do today. This fact is made more obvious when we consider possible laws that would make practicing CSR obviously less profitable than not practicing it. Consider, for example, if a law was in place that subsidized carbon emissions into our atmosphere: “For each tonne of carbon dioxide that a company emits, they will be awarded $100,000”. Further, suppose that for each tonne of carbon emissions, there is only a $1,000 loss of revenue due to consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products. Imagine that you are an oil refinery or an automobile manufacturer. Would it be more profitable to take care of the environment (or “planet” using 3P language) or would it be more profitable to pollute? Surely it would be more profitable to pollute! In fact, one should want to maximize their pollution. It is only because of taxes imposed on carbon emissions and consumer preferences for environmentally friendly products that practicing CSR (caring for the planet, in this case) is profitable.

Another, perhaps even starker example, would be a manufacturing company in Nazi Germany. Certainly, one could make a lot of money by producing for the Nazis. As we know, this sort of corporate-state alliance in the production of goods for the state was standard in Nazi Germany. Rainer Zitelmann quotes Hitler in his book Hitler: The Policies of Seduction who said,

I tell German industry, for example, ‘You have to produce such and such now.’ I then return to the Four-Year Plan. If German industry were to answer me, ‘We are not able to’, then I would say to it, ‘Fine, then I will take that over myself, but it must be done.’ But, if industry tells me ‘We will do that’, then I am very glad I do not need to take that on.

It was not only the case that businesses profited by producing for the Nazis, but were threatened with the nationalization of their industry if they did not comply. Helping the Nazis if asked might have been the only profitable way to operate your business. It should not take much to convince the reader that aiding the Nazis would scarcely constitute caring for “people” of the 3P model.

What I hope I’ve shown is that the positive correlation between CSR and profitability is not necessarily the case but only contingently so. It is only because of the legal rules, the preferences of consumers, and other social factors that CSR leads to profitability.

Why Contrast CSR with Profit-Maximization?

Students are offered a number of reasons why practicing CSR may lead to increased profitability. It may offer a competitive advantage in providing an “ethical” alternative to other companies offering similar products or services, the reputation of the company can be helped allowing them to better recover from scandals, there is better access to financing as investors are often looking to invest in ethical companies, and many more. These are intuitively correct. Certainly, I would rather buy from a company that treats its workers better or that donates to initiatives that help the poor than one that doesn’t, ceteris paribus. However, as I’ve tried to make clear above, it is only because I want to help workers and the poor that this sort of competitive advantage could arise from practicing CSR. If I did not, no such competitive advantage would arise from these practices.

What is curious is the way we sometimes talk about CSR. Our language seems to show that practicing CSR is somehow different than just aiming at profit-maximization. Consider the “triple bottom line” slogan of “people, planet, and profits” which contrasts itself with the “single bottom line” of merely profits. Clearly when we’re speaking about these ideas we see profit as opposed to CSR in a sense. But if CSR leads to greater profitability then why do we contrast the two? Why do we not say, “Go forth and make profit! CSR will result incidentally!”? For if the two are positively correlated then there is no need for distinction or contrast. The reason that we do not do this, I suspect, is that we intuitively know what I have tried to show above: sometimes CSR and profitability are opposed to one another.

It is important to make this point clear when teaching managers about CSR. If we were to simply say, “Go ahead, maximize profit! Worry about nothing else! It will all add to corporate social responsibility,” we might inadvertently be telling managers to act unethically. Think back to the example of businesses in Nazi Germany. If we are to say the opposite, “Go ahead and take care of the people and planet as much as you want! Profit will surely follow!” we may inadvertently be telling managers to misappropriate assets owned by shareholders for unprofitable purposes. Thus it is paramount that it be explained that while it is often the case that practicing CSR will result in greater profit, it is not always the case. Our intuitive distinction between CSR and profit-maximization are well-founded and we should continue to speak about the two in these terms; sometimes aligned and sometimes opposed.

Chronicles Magazine

Chronicles Magazine Dr. Walter Block has recently written

Dr. Walter Block has recently written

I would like to begin this post by pointing to a difference between

I would like to begin this post by pointing to a difference between  This article was originally meant for publication in Wilfrid Laurier University’s Newspaper,

This article was originally meant for publication in Wilfrid Laurier University’s Newspaper,  This fall, the world was treated to an excellent lecture from Hans-Hermann Hoppe from Moscow titled

This fall, the world was treated to an excellent lecture from Hans-Hermann Hoppe from Moscow titled